Gibbs free energy

| Statistical Mechanics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Thermodynamics · Kinetic theory

|

||||||||||

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy (IUPAC recommended name: Gibbs energy or Gibbs function) is a thermodynamic potential that measures the "useful" or process-initiating work obtainable from an isothermal, isobaric thermodynamic system. Just as in mechanics, where potential energy is defined as capacity to do work, similarly different potentials have different meanings. Gibbs energy is the capacity of a system to to do non-mechanical work and ΔG measures the non-mechanical work done on it. The Gibbs free energy is the maximum amount of non-expansion work that can be extracted from a closed system; this maximum can be attained only in a completely reversible process. When a system changes from a well-defined initial state to a well-defined final state, the Gibbs free energy ΔG equals the work exchanged by the system with its surroundings, minus the work of the pressure forces, during a reversible transformation of the system from the same initial state to the same final state.[1]

Gibbs energy (also referred to as ∆G) is also the chemical potential that is minimized when a system reaches equilibrium at constant pressure and temperature. As such, it is a convenient criterion of spontaneity for processes with constant pressure and temperature.

The Gibbs free energy, originally called available energy, was developed in the 1870s by the American mathematician Josiah Willard Gibbs. In 1873, in a footnote, Gibbs defined what he called the “available energy” of a body as such:

The initial state of the body, according to Gibbs, is supposed to be such that "the body can be made to pass from it to states of dissipated energy by reversible processes." In his 1876 magnum opus On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, a graphical analysis of multi-phase chemical systems, he engaged his thoughts on chemical free energy in full.

Contents |

Definitions

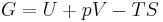

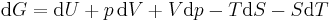

The Gibbs free energy is defined as:

- G(p,T) = U + pV − TS

which is the same as:

- G(p,T) = H − TS

where:

- U is the internal energy (SI unit: joule)

- p is pressure (SI unit: pascal)

- V is volume (SI unit: m3)

- T is the temperature (SI unit: kelvin)

- S is the entropy (SI unit: joule per kelvin)

- H is the enthalpy (SI unit: joule)

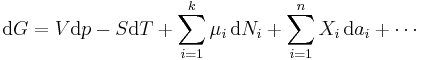

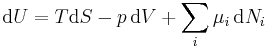

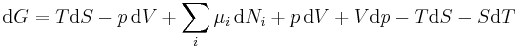

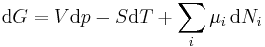

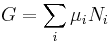

Note: H and S are thermodynamic values found at standard temperature and pressure. The expression for the infinitesimal reversible change in the Gibbs free energy, for an open system, subjected to the operation of external forces Xi, which cause the external parameters of the system ai to change by an amount dai, is given by:

where:

- μi is the chemical potential of the ith chemical component. (SI unit: joules per particle[2] or joules per mole[1])

- Ni is the number of particles (or number of moles) composing the ith chemical component.

This is one form of Gibbs fundamental equation.[3] In the infinitesimal expression, the term involving the chemical potential accounts for changes in Gibbs free energy resulting from an influx or outflux of particles. In other words, it holds for an open system. For a closed system, this term may be dropped.

Any number of extra terms may be added, depending on the particular system being considered. Aside from mechanical work, a system may, in addition, perform numerous other types of work. For example, in the infinitesimal expression, the contractile work energy associated with a thermodynamic system that is a contractile fiber that shortens by an amount −dl under a force f would result in a term fdl being added. If a quantity of charge −de is acquired by a system at an electrical potential Ψ, the electrical work associated with this is −Ψde, which would be included in the infinitesimal expression. Other work terms are added on per system requirements.[4]

Each quantity in the equations above can be divided by the amount of substance, measured in moles, to form molar Gibbs free energy. The Gibbs free energy is one of the most important thermodynamic functions for the characterization of a system. It is a factor in determining outcomes such as the voltage of an electrochemical cell, and the equilibrium constant for a reversible reaction. In isothermal, isobaric systems, Gibbs free energy can be thought of as a "dynamic" quantity, in that it is a representative measure of the competing effects of the enthalpic and entropic driving forces involved in a thermodynamic process.

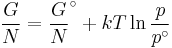

The temperature dependence of the Gibbs energy for an ideal gas is given by the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation and its pressure dependence is given by:

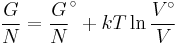

if the volume is known rather than pressure then it becomes:

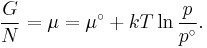

or more conveniently as its chemical potential:

In non-ideal systems, fugacity comes into play.

Derivation

The Gibbs free energy total differential natural variables may be derived via Legendre transforms of the internal energy.

.

.

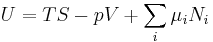

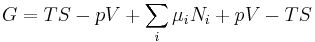

Because S, V, and Ni are extensive variables, Euler's homogeneous function theorem allows easy integration of dU:[5]

.

.

The definition of G from above is

.

.

Taking the total differential, we have

.

.

Replacing dU with the result from the first law gives[5]

.

.

The natural variables of G are then p, T, and {Ni}. Because some of the natural variables are intensive, dG may not be integrated using Euler integrals as is the case with internal energy. However, simply substituting the result for U into the definition of G gives a standard expression for G:[5]

.

.

Overview

In a simple manner, with respect to STP reacting systems, a general rule of thumb is:

| “ | Every system seeks to achieve a minimum of free energy. | ” |

Hence, out of this general natural tendency, a quantitative measure as to how near or far a potential reaction is from this minimum is when the calculated energetics of the process indicate that the change in Gibbs free energy ΔG is negative. In essence, this means that such a reaction will be favoured and will release energy. The energy released equals the maximum amount of work that can be performed as a result of the chemical reaction. In contrast, if conditions indicated a positive ΔG, then energy—in the form of work—would have to be added to the reacting system to make the reaction go.

The equation can also be seen from the perspective of both the system and its surroundings (the universe). For the purposes of calculation, we assume the reaction is the only reaction going on in the universe. Thus the entropy released or absorbed by the system is actually the entropy that the environment must absorb or release respectively. Thus the reaction will only be allowed if the total entropy change of the universe is equal to zero (an equilibrium process) or positive. The input of heat into an "endothermic" chemical reaction (e.g. the elimination of cyclohexanol to cyclohexene) can be seen as coupling an inherently unfavourable reaction (elimination) to a favourable one (burning of coal or the energy source of a heat source) such that the total entropy change of the universe is more than or equal to zero, making the Gibbs free energy of the coupled reaction negative.

History

The quantity called "free energy" is a more advanced and accurate replacement for the outdated term affinity, which was used by chemists in previous years to describe the force that caused chemical reactions. The term affinity, as used in chemical relation, dates back to at least the time of Albertus Magnus in 1250.

From the 1998 textbook Modern Thermodynamics[6] by Nobel Laureate and chemistry professor Ilya Prigogine we find: "As motion was explained by the Newtonian concept of force, chemists wanted a similar concept of ‘driving force’ for chemical change. Why do chemical reactions occur, and why do they stop at certain points? Chemists called the ‘force’ that caused chemical reactions affinity, but it lacked a clear definition."

During the entire 18th century, the dominant view with regard to heat and light was that put forth by Isaac Newton, called the Newtonian hypothesis, which states that light and heat are forms of matter attracted or repelled by other forms of matter, with forces analogous to gravitation or to chemical affinity.

In the 19th century, the French chemist Marcellin Berthelot and the Danish chemist Julius Thomsen had attempted to quantify affinity using heats of reaction. In 1875, after quantifying the heats of reaction for a large number of compounds, Berthelot proposed the principle of maximum work, in which all chemical changes occurring without intervention of outside energy tend toward the production of bodies or of a system of bodies which liberate heat.

In addition to this, in 1780 Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace laid the foundations of thermochemistry by showing that the heat given out in a reaction is equal to the heat absorbed in the reverse reaction. They also investigated the specific heat and latent heat of a number of substances, and amounts of heat given out in combustion. In a similar manner, in 1840 Swiss chemist Germain Hess formulated the principle that the evolution of heat in a reaction is the same whether the process is accomplished in one-step process or in a number of stages. This is known as Hess' law. With the advent of the mechanical theory of heat in the early 19th century, Hess’s law came to be viewed as a consequence of the law of conservation of energy.

Based on these and other ideas, Berthelot and Thomsen, as well as others, considered the heat given out in the formation of a compound as a measure of the affinity, or the work done by the chemical forces. This view, however, was not entirely correct. In 1847, the English physicist James Joule showed that he could raise the temperature of water by turning a paddle wheel in it, thus showing that heat and mechanical work were equivalent or proportional to each other, i.e., approximately,  . This statement came to be known as the mechanical equivalent of heat and was a precursory form of the first law of thermodynamics.

. This statement came to be known as the mechanical equivalent of heat and was a precursory form of the first law of thermodynamics.

By 1865, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius had shown that this equivalence principle needed amendment. That is, one can use the heat derived from a combustion reaction in a coal furnace to boil water, and use this heat to vaporize steam, and then use the enhanced high-pressure energy of the vaporized steam to push a piston. Thus, we might naively reason that one can entirely convert the initial combustion heat of the chemical reaction into the work of pushing the piston. Clausius showed, however, that we must take into account the work that the molecules of the working body, i.e., the water molecules in the cylinder, do on each other as they pass or transform from one step of or state of the engine cycle to the next, e.g., from (P1,V1) to (P2,V2). Clausius originally called this the “transformation content” of the body, and then later changed the name to entropy. Thus, the heat used to transform the working body of molecules from one state to the next cannot be used to do external work, e.g., to push the piston. Clausius defined this transformation heat as dQ = TdS.

In 1873, Willard Gibbs published A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces, in which he introduced the preliminary outline of the principles of his new equation able to predict or estimate the tendencies of various natural processes to ensue when bodies or systems are brought into contact. By studying the interactions of homogeneous substances in contact, i.e., bodies, being in composition part solid, part liquid, and part vapor, and by using a three-dimensional volume-entropy-internal energy graph, Gibbs was able to determine three states of equilibrium, i.e., "necessarily stable", "neutral", and "unstable", and whether or not changes will ensue. In 1876, Gibbs built on this framework by introducing the concept of chemical potential so to take into account chemical reactions and states of bodies that are chemically different from each other. In his own words, to summarize his results in 1873, Gibbs states:

In this description, as used by Gibbs, ε refers to the internal energy of the body, η refers to the entropy of the body, and ν is the volume of the body.

Hence, in 1882, after the introduction of these arguments by Clausius and Gibbs, the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz stated, in opposition to Berthelot and Thomas’ hypothesis that chemical affinity is a measure of the heat of reaction of chemical reaction as based on the principle of maximal work, that affinity is not the heat given out in the formation of a compound but rather it is the largest quantity of work which can be gained when the reaction is carried out in a reversible manner, e.g., electrical work in a reversible cell. The maximum work is thus regarded as the diminution of the free, or available, energy of the system (Gibbs free energy G at T = constant, P = constant or Helmholtz free energy F at T = constant, V = constant), whilst the heat given out is usually a measure of the diminution of the total energy of the system (Internal energy). Thus, G or F is the amount of energy “free” for work under the given conditions.

Up until this point, the general view had been such that: “all chemical reactions drive the system to a state of equilibrium in which the affinities of the reactions vanish”. Over the next 60 years, the term affinity came to be replaced with the term free energy. According to chemistry historian Henry Leicester, the influential 1923 textbook Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Reactions by Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall led to the replacement of the term “affinity” by the term “free energy” in much of the English-speaking world.

What does the term ‘free’ mean?

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the theory of heat, i.e., that heat is a form of energy having relation to vibratory motion, was beginning to supplant both the caloric theory, i.e., that heat is a fluid, and the four element theory, in which heat was the lightest of the four elements. Many textbooks and teaching articles during these centuries presented these theories side by side. In a similar manner, during these years, heat was beginning to be distinguished into different classification categories, such as “free heat”, “combined heat”, “radiant heat”, specific heat, heat capacity, “absolute heat”, “latent caloric”, “free” or “perceptible” caloric (calorique sensible), among others.

In 1780, for example, Laplace and Lavoisier stated: “In general, one can change the first hypothesis into the second by changing the words ‘free heat, combined heat, and heat released’ into ‘vis viva, loss of vis viva, and increase of vis viva.’” In this manner, the total mass of caloric in a body, called absolute heat, was regarded as a mixture of two components; the free or perceptible caloric could affect a thermometer, whereas the other component, the latent caloric, could not.[7] The use of the words “latent heat” implied a similarity to latent heat in the more usual sense; it was regarded as chemically bound to the molecules of the body. In the adiabatic compression of a gas, the absolute heat remained constant by the observed rise of temperature, indicating that some latent caloric had become “free” or perceptible.

Thus, in traditional use, the term “free” was attached to Gibbs free energy, i.e., for systems at constant pressure and temperature, or to Helmholtz free energy, i.e., for systems at constant volume and temperature, to mean ‘available in the form of useful work.’[1] With reference to the Gibbs free energy, we add the qualification that it is the energy free for non-volume work.[8]

An increasing number of books and journal articles do not include the attachment “free”, referring to G as simply Gibbs energy (and likewise for the Helmholtz energy). This is the result of a 1988 IUPAC meeting to set unified terminologies for the international scientific community, in which the adjective ‘free’ was supposedly banished.[9] This standard, however, has not yet been universally adopted, and many published articles and books still include the descriptive ‘free’.

Free energy of reactions

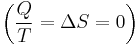

To derive the Gibbs free energy equation for an isolated system, let Stot be the total entropy of the isolated system, that is, a system that cannot exchange heat or mass with its surroundings. According to the second law of thermodynamics:

and if ΔStot = 0 then the process is reversible. The heat transfer Q vanishes for an adiabatic system. Any adiabatic process that is also reversible is called an isentropic  process.

process.

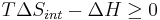

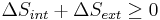

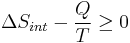

Now consider systems, having internal entropy Sint. Such a system is thermally connected to its surroundings, which have entropy Sext. The entropy form of the second law applies only to the closed system formed by both the system and its surroundings. Therefore a process is possible if

.

.

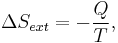

If Q is heat transferred to the system from the surroundings, so −Q is heat lost by the surroundings

- so that

corresponds to entropy change of the surroundings.

corresponds to entropy change of the surroundings.

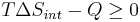

- We now have:

- Multiply both sides by T:

Q is heat transferred to the system; if the process is now assumed to be isobaric, then Qp = ΔH:

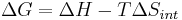

ΔH is the enthalpy change of reaction (for a chemical reaction at constant pressure). Then

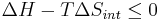

for a possible process. Let the change ΔG in Gibbs free energy be defined as

(eq.1)

(eq.1)

Notice that it is not defined in terms of any external state functions, such as ΔSext or ΔStot. Then the second law becomes, which also tells us about the spontaneity of the reaction:

favoured reaction (Spontaneous)

favoured reaction (Spontaneous) Neither the forward nor the reverse reaction prevails (Equilibrium)

Neither the forward nor the reverse reaction prevails (Equilibrium) disfavoured reaction (Nonspontaneous)

disfavoured reaction (Nonspontaneous)

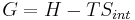

Gibbs free energy G itself is defined as

(eq.2)

(eq.2)

but notice that to obtain equation (2) from equation (1) we must assume that T is constant. Thus, Gibbs free energy is most useful for thermochemical processes at constant temperature and pressure: both isothermal and isobaric. Such processes don't move on a P-V diagram, such as phase change of a pure substance, which takes place at the saturation pressure and temperature. Chemical reactions, however, do undergo changes in chemical potential, which is a state function. Thus, thermodynamic processes are not confined to the two dimensional P-V diagram. There is a third dimension for n, the quantity of gas. For the study of explosive chemicals, the processes are not necessarily isothermal and isobaric. For these studies, Helmholtz free energy is used.

If an isolated system (Q = 0) is at constant pressure (Q = ΔH), then

Therefore the Gibbs free energy of an isolated system is:

and if ΔG ≤ 0 then this implies that ΔS ≥ 0, back to where we started the derivation of ΔG

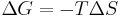

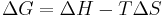

Useful identities

for constant temperature remember by: "goldfish are hell without tartar sauce"

for constant temperature remember by: "goldfish are hell without tartar sauce"

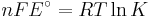

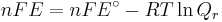

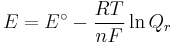

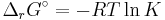

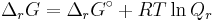

(see Chemical equilibrium).

(see Chemical equilibrium).

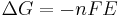

and rearranging gives

which relates the electrical potential of a reaction to the equilibrium coefficient for that reaction.

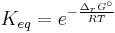

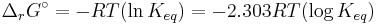

where

ΔG = change in Gibbs free energy, ΔH = change in enthalpy, T = absolute temperature, ΔS = change in entropy, R = gas constant, ln = natural logarithm, ΔrG = change of reaction in Gibbs free energy, ΔrG° = standard change of reaction in Gibbs free energy, K = equilibrium constant, Qr = reaction quotient, n = number of electrons per mole product, F = Faraday constant (coulombs per mole), and E = electric potential of the reaction. Moreover, we also have:

which relates the equilibrium constant with Gibbs free energy.

Standard change of formation

The standard Gibbs free energy of formation of a compound is the change of Gibbs free energy that accompanies the formation of 1 mole of that substance from its component elements, at their standard states (the most stable form of the element at 25 degrees Celsius and 100 kilopascals). Its symbol is ΔfG˚.

All elements in their standard states (oxygen gas, graphite, etc.) have 0 standard Gibbs free energy change of formation, as there is no change involved.

- ΔrG = ΔrG˚ + RT ln Qr; Qr is the reaction quotient.

At equilibrium, ΔrG = 0 and Qr = K so the equation becomes ΔrG˚ = −RT ln K; K is the equilibrium constant.

Table of selected substances[10]

| Substance | State | ΔfG°(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| NH3 | g | −3.976 |

| H2O | l | −56.69 |

| H2O | g | −54.64 |

| CO2 | g | −94.26 |

| CO | g | −32.81 |

| CH4 | g | −12.14 |

| C2H6 | g | −7.86 |

| C3H8 | g | −5.614 |

| C8H18 | g | 4.14 |

| C10H22 | g | 8.23 |

See also

- Calphad

- Enthalpy

- Entropy

- Free entropy

- Grand potential

- Helmholtz free energy

- Thermodynamic free energy

- Thermodynamics

- Josiah Willard Gibbs

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6.

- ↑ Chemical Potential - IUPAC Gold Book

- ↑ Müller, Ingo (2007). A History of Thermodynamics - the Doctrine of Energy and Entropy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-46226-2.

- ↑ Katchalsky, A.; Curran, Peter, F. (1965). Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics in Biophysics. Harvard University Press. CCN 65-22045.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Salzman, William R. (2001-08-21). "Open Systems". Chemical Thermodynamics. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. http://web.archive.org/web/20070707224025/http://www.chem.arizona.edu/~salzmanr/480a/480ants/opensys/opensys.html. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Kondepudi, Dilip; Prigogine, Ilja (1998). Modern Thermodynamics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-0471-97394-2 (pbk). Chapter 4, Section 1, Paragraph 2 (page 103)

- ↑ Mendoza, E. (1988). Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire – and other Papers on the Second Law of Thermodynamics by E. Clapeyron and R. Carnot. Dover Publications, Inc.. ISBN 0-486-44641-7.

- ↑ Reiss, Howard (1965). Methods of Thermodynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-69445-3.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Atomspheric Chemistry, J. G. (1990). "Glossary of Atmospheric Chemistry Terms (Recommendations 1990)". Pure Appl. Chem. 62: 2167–2219. doi:10.1351/pac199062112167. http://www.iupac.org/publications/pac/1990/pdf/6211x2167.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-28. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Physicochemical Symbols Terminology and Units (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (2nd Edition). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. pp. 48. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. http://www.iupac.org/publications/books/gbook/green_book_2ed.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-28. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Quantities and Units in Clinical Chemistry, H. P.; International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Committee on Quantities and Units (1996). "Glossary of Terms in Quantities and Units in Clinical Chemistry (IUPAC-IFCC Recommendations 1996)". Pure Appl. Chem. 68: 957–1000. doi:10.1351/pac199668040957. http://www.iupac.org/publications/pac/1996/pdf/6804x0957.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ Handbook of chemistry and physics, 1960, p.1882-1915, p.1919-1921, 42nd ed., Harrison

External links

- IUPAC definition (Gibbs energy)

- Gibbs energy - Florida State University

- Gibbs Free Energy - Eric Weissteins World of Physics

- Entropy and Gibbs Free Energy - www.2ndlaw.com

- Gibbs Free Energy - Georgia State University

- Gibbs Free Energy Java Applet - University of California, Berkeley

- Gibbs Free Energy - Illinois State University